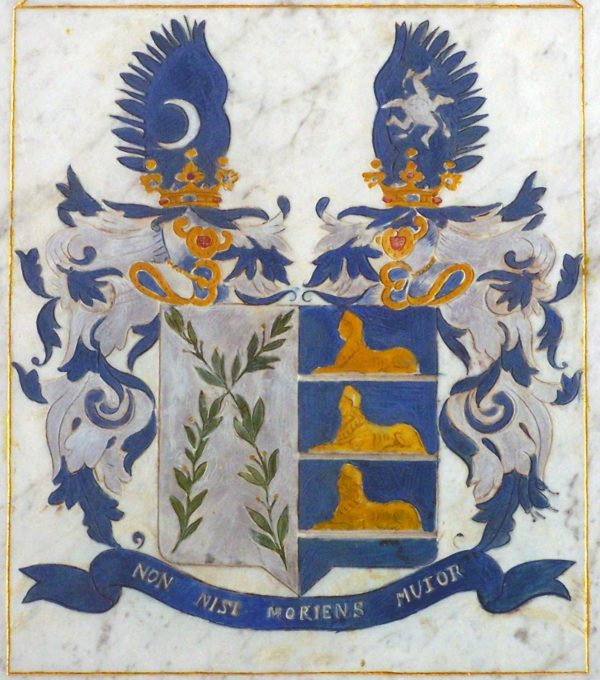

Coat of arms of the Lavrin family in Vipava

VIPAVA, CEMETERY

Location of the coat of arms: tombstone

One of the main attractions in Vipava Cemetery is a pair of ancient Egyptian sarcophagi in the mausoleum of the Lavrin-Hrovatin family. They were transferred there in 1846 by Anton Ritter von Lavrin (also Laurin), a famous Egyptologist and diplomat from Vipava (Ital. Vipacco, Germ. Wippach). He was born in 1789 as the son of Bartholomeus Lavrin, a local landholder and miller, and Josefa Uršič (Urschitsch). On completing the grammar school in Gorizia (Germ. Görz), he pursued his theological studies at the Ljubljana lyceum and in 1816 also completed his law studies at the University of Vienna. His mastery of foreign languages secured him his first employment with the Ministry of Economy and Trade, under which he became the administrative consul in Palermo in 1822 and then also in Messina and Naples. Six years later (in 1828), he became the Austrian consul-general in Palermo and in 1834 in Alexandria. When a dispute broke out between the Turkish government and Egyptian Viceroy Muhammad Ali in 1840, Lavrin interceded diplomatically and led the opposing sides to reach a compromise. As a token of recognition, the sultan conferred on him the Order of Glory (Nichani-Iftihar), and the Austrian emperor the third class of the Order of the Iron Crown, accompanied by the hereditary title of knighthood.

On his elevation to nobility, Lavrin selected a very intriguing coat of arms, which can now also be seen carved on the mausoleum in Vipava. The sinister field features three sphynxes symbolizing his interest in ancient Egypt, and the dexter field displays a pair of entwined olive branches—one dry and the other green and bearing fruit, perhaps representing the intertwining of the past and the present. What especially catches the eye, however, is a silver symbol on the wings growing from the sinister crown. It is the so-called trinacria, the emblem of Sicily appearing as Medusa’s head (with snakes as hair) surrounded by three bent legs forming a rotational symmetry. Lavrin undoubtedly selected this symbol in memory of his first diplomatic mission to Sicily. On the wings growing from the dexter crown a silver halfmoon is depicted as the emblem of the Ottoman Empire, which also played an important role in Lavrin’s diplomatic career. Below the escutcheon runs a blue ribbon with the Latin inscription NON NISI MORIENS MUTOR (I do not change than by death).

Despite running into a dispute with the Egyptian government based on which he was even recalled for a while, Lavrin remained in Alexandria until 1849. There, among other things, he met with Ignatius Knoblecher, the renowned missionary and researcher of the White Nile. In his Alexandrian villa, he kept a host of souvenirs and monuments from the Egyptian past. He donated many to the Art History Museum in Vienna and the Provincial Museum in Ljubljana, including a wooden coffin with the mummy of the Egyptian priest Akesuita, now held by the National Museum of Slovenia. Due to his remarkable accomplishments in studying ancient Egypt, he is even considered to have been “the most important patron of the Habsburg collection of Egypt’s ancient history.” In 1853, Lavrin sold a large part of the collection to Archduke Maximilian for his Miramar Castle in Trieste. On its pier, one can still see the red granite sculpture of a sphynx from Lavrin’s collection. Finally, Lavrin also had a pair of sarcophagi transported to his native Vipava to serve as the final resting place for his parents and son Albert Alexander.

Sources:

Rugále, Mariano in Preinfalk, Miha: Blagoslovljeni in prekleti. 2. del: Po sledeh mlajših plemiških rodbin na Slovenskem. Ljubljana: Viharnik, 2012, str. 95–98.